By NH Chan

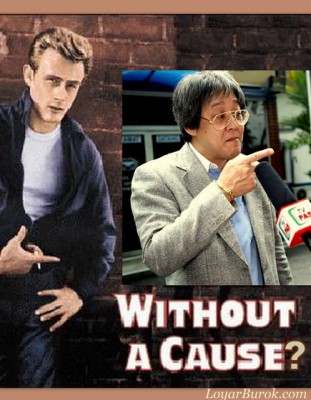

A deliberation on whether Matthias Chang was a victim of judicial oppression through an examination of the law of contempt; from its coming to being to its evolution to what it is today and how it applies to Matthias Chang’s unruly behaviour in court – in 2 parts.

In the Sun newspaper of Friday April 2 2010 I came across this story:

Dr. M’s ex-aide starts jail term for contemptKUALA LUMPUR: Matthias Chang, former political secretary of ex-premier Tun Dr. Mahathir Mohamad, was sent to prison after he refused to pay a RM20,000 fine for contempt of court.

Chang was served the committal order by the High Court before he was taken to Kajang prison.The judge says that Chang had committed contempt in the face of the court.

The lawyer was cited for contempt of court on March 25 when he failed to apologise to the court during cross-examination in his defamation suit against American Express (Malaysia).

The committal order stated: “At about 2.30pm to day (March 25) … when the court refused your request to address the court as a witness, you lost your cool and walked out of the witness box and thereafter left the court during the proceedings. Your conduct is a contempt in the face of the court by virtue of Order 52 (1A) of the Rules of the High Court.”

Judge Noor Azian Shaari had ordered Chang to pay a fine of RM20,000 within seven days, in default [to serve a] month’s jail sentence.

I will first tell about how the law of contempt came into being. Then I will tell about how it had evolved into what it has become in modern times. But before that you may wish to know,

What is contempt in the face of the court?

If you have read my book How to Judge the Judges, 2nd edition, Sweet & Maxwell Asia, you will come across this passage on page 61:Contempt in the face of the CourtThis was what the judge Noor Azian Shaari meant when she told Matthias Chang “Your conduct is a contempt in the face of the court.” Chang had disrupted court proceedings as a witness when he walkout in a huff.

If you attack the character or conduct of a judge it could be termed a contempt by scandalizing the judiciary. If you make the same attack in court or if you disrupt proceedings in court it is called contempt in the face of the court.

The difference between contempt by scandalising the judiciary and contempt in the face of the court is that the latter is dealt with summarily, that is to say, done or made immediately and without following the normal procedures – this is the dictionary meaning. And this is how Lee Hun Hoe CJ (Borneo) put it in Cheah Cheng Hoc v Public Prosecutor [1986] 1 MLJ 299 (SC), at p 301:

The power of summary punishment is a necessary power to maintain the dignity and authority of the Judge and to ensure a fair trial. It should be exercised with scrupulous care and only when the case is clear and beyond reasonable doubt. As Lord Denning, MR said in Balogh v Crown Court [1974] 3 All ER 283, at 288:

“It is to be exercised by the judge of his own motion only when it is urgent and imperative to act immediately – so as to maintain the authority of the court – to prevent disorder- to enable witnesses to be free from fear – and jurors being improperly influenced – and the like …”This power must be used sparingly but fearlessly when necessary to prevent obstruction of justice. We feel that we must leave the exercise of this awesome power to the good sense of our judge. We will interfere when this power is misused.

Now that we know what is contempt in the face of the court better than any other uninstructed person, we should not listen to a non-lawyer, like Che Det, giving pompous legal advice and telling-off the judge that “no one should be the prosecutor, the judge and the executioner.” Doesn’t our former prime minister know that summary decisions are part of living in a civilized society? The umpire in a badminton match does it all the time, so does the referee in a soccer match and other sporting activities, but most of all, and he should know as he was a parliamentarian, the speaker of the House of Representatives or Legislative Assembly does it all the time at every sitting; they are all, to use his own words, “prosecutor, judge and executioner.”

Contempt in the face of the court means “the power of summary punishment to be exercised by the judge of his own motion only when it is urgent and imperative to act immediately” so as to prevent – as in the case of Matthias Chang – disruption of the court proceedings. This is a necessary power to be exercised only in the most pressing cases so as to deal with the circumstances or situations stated by Lord Denning in Balogh v Crown Office.

The history of this awesome power of the judges

But first let me relate the historical evolution of this awesome power of a judge at common law. I won’t say it is a draconian power because nowadays, that is, ever since 1936- since Ambard v A-G for Trinidad & Tobago, a more tolerant attitude is taken by the common law towards critics of the judiciary.-

On how the law of contempt came into being

At the beginning, before 1936, it was an excessively harsh power – one could say it was a draconian power. But why was it so? Because during the time of despotic kings of England, the king’s judges were lions under the throne of the king, and they were wielding the power of the king in the administration of the king?s notion of justice – do remember that the common law of England is entwined in the history of England. This was how Mr. Justice Wilmot (in an opinion which was not delivered because the prosecution was dropped) explained the purpose of this law in R v Almon 97 ER 94, 100 (1765):

The arraignment of the justice of the Judges is arraigning the King’s justice; it is an impeachment of his wisdom and goodness in the choice of his Judges, and excites in the minds of the people a general dissatisfaction with all judicial determinations and indisposes their minds to obey them; and whenever men’s allegiance to the laws is so fundamentally shaken, it is the most fatal and most dangerous obstruction of justice, and, in my opinion, calls out for a more rapid and immediate redress than any other obstruction whatsoever; not for the sake of the Judges, as private individuals, but because they are the channels by which the King’s justice is conveyed to the people.

In 1788 in the case of R v Watson 2 Term Reports (Durnford and East) 199, 205 (1788) Mr. Justice Buller expressed similar sentiments:

Nothing can be of greater importance to the welfare of the public than to put a stop to the animadversions and censures which are so frequently made on courts of justice in this country. They can be of no service, and may be attended with the most mischievous consequences. … When a person has recourse … by publications in print, or by any other means, to calumniate the proceedings of a Court of justice, the obvious tendency of it is to weaken the administration of justice, and in consequence to sap the very foundation of the Constitution itself.

-

And how from such beginnings the law of contempt had evolved to what it is today

Despite the demise of the reign of despotic kings where it ended with the flight of King James II from the realm – James II was the last of the Stuart Kings of England (1603-1714) – “the grandiloquent fear that criticism of the courts may endanger civilization” had continued right up to the early twentieth century. “The branch of contempt of court known as ’scandalising the judiciary’ served to inhibit criticism of the courts by laymen. To a limited extent it remains a fetter on freedom of expression about judicial performance.” – see Pannick, Judges, page 109.

In R v Gray [1900] 2 QB 36, 40, Lord Russell of Killowen CJ laid down the law of contempt in this way:

“Any act done or writing published calculated to bring a Court or a judge of the Court into contempt, or to lower his authority, is a contempt of court.”

This is nicely summed up by David Pannick in his book Judges, at page 110:

“The grandiloquent fear that criticism of the courts may endanger civilization has, in the twentieth century, continued to lead to the punishment of persons who have insulted members of the judiciary or impugned their impartiality.”

The book then goes on to say, pp 110-112:

English law remained unwilling to leave it to public opinion to assess whether criticism of the judiciary had any basis.

Mr. Justice Darling was the presiding judge at the Birmingham Spring Assizes in 1900. Before the start of a trial for obscene libel, he warned the press that they should not publish indecent accounts of the evidence. After the conviction and sentence of the defendant in the criminal case, Mr Gray wrote and published in the Birmingham Daily Argus, of which he was the Editor, an article [in which he described] how Mr. Justice Darling,

” … filled in a pleasant five minutes yesterday. … Mr. Justice Darling … [warned] the Press against the printing of indecent evidence. His diminutive Lordship positively glowed with judicial self-consciousness. … He felt himself bearing on his shoulders the whole fabric of public decency. … There is not a journalist in Birmingham who has anything to learn from the impudent little man in horsehair, a microcosm of conceit and empty-headedness. … One of Mr. Justice Darling’s biographers states that ‘an eccentric relative left him much money.’ That misguided testator spoiled a successful bus conductor.”

This splendid piece of invective effectively punctured the vain pretensions of Mr. Justice Darling whose injudicious behaviour on the Bench was frequently a disgrace. …

Mr. Gray’s prose was not appreciated by the courts. He was brought before the Queen’s Bench Division charged with contempt of court. He swore a groveling affidavit of apology, no doubt on sensible legal advice that otherwise there would be even more serious consequences for him. …

Lord Russell, the Lord Chief Justice, … gave a solemn judgment, noting that it was “an article of scurrilous abuse of a judge in his character of judge – scurrilous abuse in reference to the conduct of a judge while sitting under the Queen’s Commission, and scurrilous abuse published in a newspaper in the town in which he was still sitting under the Queen’s Commission.” He concluded that there was no doubt that the article amounted to a contempt of court. … he was fined 100 pounds and ordered to pay the costs.

The above case was reported in the Law Reports series as R v Gray [1900] 2 QB 36, 39-42. This is the case where Lord Russell of Killowen had laid down the draconian law of contempt which had stifled criticisms of the judiciary in the early part of the twentieth century until the judgment of Lord Atkin in Ambard v A-G for Trinidad & Tobago ended it in 1936.

Here are a couple of examples of those pre-1936 cases:

i) In R v Vidal, The Times 14 Oct. 1922 a dissatisfied litigant who believed that the President of the Probate, Divorce and Admiralty Division of the High Court was a party to a conspiracy against him walked up and down outside the Law Courts with a placard accusing the judge of being “a traitor to his duty.” He was sentenced to four months’ imprisonment.

ii) In R v Freeman, The Times 18 Nov 1925 another dissatisfied litigant sent a letter to Mr. Justice Roche, who had decided a case against him, accusing the judge of being “a liar, a coward, a perjurer.” He was held of being in contempt of court.

Editorial Note: In Part 2 tomorrow - How does the law of contempt in the face of the court apply toMatthias Chang?

courtesy of Loyarburok

No comments:

Post a Comment