By NH Chan

A deliberation on whether Matthias Chang was a victim of judicial oppression through an examination of the law of contempt; from its coming to being to its evolution to what it is today and how it applies to Matthias Chang’s unruly behaviour in court – in 2 parts.

Continued from Part 1

- But the tide of the pompous attitude of the judges in their own conceit and self-importance changed abruptly in 1936

At page 114 of David Pannick’s book Judges: “More recently, courts have emphasised that only in very exceptional cases will charges of contempt be brought against those who criticise the judiciary.”

Lord Atkin explained it in the Privy Council case of Ambard v A-G for Trinidad and Tobago [1936] AC 322, at p 335:

… whether the authority and position of an individual judge, or the due administration of justice, is concerned, no wrong is committed by any member of the public who exercises the ordinary right of criticising, in good faith, in private or public, the public act done in the seat of justice. The path of criticism is a public way: the wrong-headed are permitted to err therein; provided that members of the public abstain from imputing improper motives to those taking part in the administration of justice, and are genuinely exercising a right of criticism, and not acting in malice or attempting to impair the administration of justice, they are immune. Justice is not a cloistered virtue: she must be allowed to suffer the scrutiny and respectful, even though outspoken, comments of ordinary men.

This case was decided in 1936, so it is embodied in our common law of contempt by virtue of section 3(1) of the Civil Law Act 1956 which says:

(1) Save so far as other provision has been made or may hereafter be made by any written law in force in Malaysia, the court shall:

(a) in Peninsular Malaysia or any part thereof, apply the common law of England and the rules of equity as administered in England on April 7, 1956;

(b) in Sabah, apply the common law of England and the rules of equity, … as administered or in force in England on December 1, 1951;

(c) in Sarawak, apply the common law of England and the rules of equity, … as administered or in force in England on December 12, 1949, …

(b) in Sabah, apply the common law of England and the rules of equity, … as administered or in force in England on December 1, 1951;

(c) in Sarawak, apply the common law of England and the rules of equity, … as administered or in force in England on December 12, 1949, …

But tragically, to the many who have suffered at the hands of the judges, the blame has to be placed on our Supreme Court for being under the delusion that the common law of England on contempt was that as stated in R v Gray [1900] 2 QB 36 and they have applied it as the common law which applies in this country by virtue of section 3(1) of the Civil Law Act 1956. They were oblivious of Ambard v A-G for Trinidad and Tobago which was decided in 1936 and which has since then completely changed the way the common law world looked at the law of contempt of scandalising the judiciary.

The result that Ambard v A-G for Trinidad & Tobago has brought about is that all previous Supreme Court cases that depended on R v Gray were decided per incuriam (by oversight, failure to notice).

The effect is that all those cases of contempt mentioned in the judgment of the Supreme Court in Attorney-General, Malaysia v Manjeet Singh [1990] 1 MLJ 167 have failed to apply the common law of England on contempt as it stood in 1956 – in other words, our courts by applying R v Gray, a 1900 decision, have consistently applied an obsolete law.

The judgment of Mohamad Yusuff SCJ at pp 177, 178 belies the mediocrity of the judgment itself. He said:

The Supreme Court has this far consistently applied the common law principle of contempt of court as seen in the judgments of these cases, viz: Arthur Lee Meng Kwang v Faber Merlin (M) Bhd & Ors [1986] 1 MLJ 193, Lim Kit Siang v Dato’ Mahathir Mohamad [1987] 1 MLJ 383 and Trustee of Leong San Tong Kongsi (Penang) Registered & Ors v SM Idris [1990] 1 MLJ 273. All these cases dealt with contempt in scandalizing the court. … the common law, as has been expounded, applied and decided by our courts after April 7, 1956, by virtue of the Civil Law Act 1956, has become part of our law.

… On the law applicable to this case … as mentioned earlier, the principle of common law of contempt as stated in R v Gray [1900] 2 QB 36 still applies in our country.

This judge and all the other judges who have decided the cases of Manjeet Singh, Arthur Lee, Lim Kit Siang and Leong San Tong Kongsi did not realize that R v Gray had been superseded by Ambard v A-G for Trinidad & Tobago. This judgment of the Privy Council as to the obsolescence of the offence of scandalising the judiciary has demonstrated that R v Gray is no longer good law. (Emphasis by LoyarBurok)

Therefore, the common law of England on the law of contempt of scandalising the judiciary as it stood in 1956 is Ambard v A-G for Trinidad & Tobago; the judgment of the Privy Council by Lord Atkin allows for criticism of the judiciary even in the ferocity of the language used. The common law of England on the law of contempt as administered in England in 1956 is not R v Gray (which is obsolete) but Ambard v A-G for Trinidad & Tobago.

Poor Arthur Lee, and poor Lim Kit Siang, and poor Manjeet Singh and poor Murray Hiebert (Murray Hiebert v Chandra Sri Ram [1999] 4 MLJ 321), they have all been convicted of the offence of scandalising the judiciary on an obsolete law.

Tragically, the obsolescence of the offence of scandalizing the judiciary has escaped the uninspired minds of our judges.

Mr. Martin Jalleh has suggested that I be charged with contempt of court. I think it was an unreasonable request because such an event would put the entire judiciary in a quandary. Those cases, such as Arthur Lee, Lim Kit Siang, Manjeet Singh, and even Murray Hiebert are over, bar the shouting, – the phrase is used when any controversial event is said to be technically settled but arguments about the outcome continue, albeit with little effect on the result: see Red Herrings and White Elephants, Albert Jack, Metro Publishing Ltd, London, 2004. I would suggest that it is best to let sleeping dogs (or should I say, lions) lie.

Even our former prime minister Tun Mahathir admitted in Che Det that when he gave his opinion that the judge should not be prosecutor, judge, and executioner in Matthias Chang’s case – he did so with trepidation. Actually, he has nothing to worry about. We are both on the same boat. Our defence is this:

This briefly tells the history and evolution of the law of contempt up to the present time.By virtue of section 3(1)(a) of the Civil Law Act 1956, the common law of Peninsular Malaysia is the common law of England as administered in England on April 7, 1956. The common law of England on the law of contempt of scandalising the judiciary as administered in England in 1956 is Ambard v A-G for Trinidad & Tobago which allows for criticism of the judiciary even in the ferocity of the language used.

We can now proceed to look at Matthias Chang’s case with a broader and better understanding.

How does the law of contempt in the face of the court apply to Matthias Chang?

As far back as in 1527 there is this tale of Sergeant Roo, “a great lawyer of that time, more eager to show his wit than to be made a Judge,” who had composed a satire on the abuses of the law for which Lord Chancellor Wolsey was responsible. The satire was delivered in the presence of the King. Roo was summarily dispatched to prison – see Judges by David Pannick, Barrister; Fellow of All Souls College, Oxford, OUP, 1987, at page 105 to which he has also included the rider:Nowadays a more tolerant attitude is taken towards critics of the judiciary. Nevertheless, lawyers and non-lawyers remain reluctant to emulate the critical approach of Sergeant Roo.In times past – as I have explained in the history above – lawyers, “If they have suggestions for reform of the judiciary, or comments to make on judicial performance, they whisper them to each other over lunch in the Middle Temple or in professional journals remote from the public gaze. Such heresies are expressed cautiously, in deferential language.” – see Judges, pp 105, 106 where it also said:

In one case, after Lord Mansfield (Chief Justice of the King’s Bench, 1756-88) had given judgment for a Bench of four judges, he asked Sergeant Hill, who appeared for the unsuccessful party, to “tell us your real opinion and whether you don’t think we are right.” Hill replied that “he always thought it his duty to do what the Court desired and … he … did not think that there were four men in the world who could have given such an ill-sounded judgment …

…

More often, it is only in fiction that the conventions of politeness to judges are defied. The judges before whom John Mortimer’s Rumpole appears are perverse and malign. They are ignorant of the ways of the world. They are differential or rude to witnesses depending on the social status of those who have the misfortune to give evidence in their courts. … Only a barrister of Rumpole’s experience (and lack of ambition) can afford to reply in kind to the discourtesy emanating from that fictional Bench.Ever heard of the expression “truth is stranger than fiction”? In this country we have experienced for real perverse and malign judges, not the fictional ones experienced by John Mortimer’s Rumpole.

In 1680, Nathaniel Redding accused two judges of “oppression” and was condemned in Court to pay the King 500 pounds and lie in prison till he paid it, see Nathaniel Redding’s Case, Sir Thomas Raymond’s Reports 376 n. (1680). Later that term the court remitted the fine and the sentence of imprisonment.

In the Matter of Thomas James Wallace (1866) LR 1 PC 283, a Nova Scotia lawyer wrote a letter to the Chief Justice complaining that “I can’t help thinking that I am not fairly dealt with by the Court or Judges.” He added that he “could also recall cases where the decision was, I believe, largely influenced, if not wholly based, upon information received privately from the wife of one of the parties by the judge. Is this justice?” Lord Westbury, in the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, remarked that this “undoubtedly was a letter of a most reprehensible kind … a contempt of court, which it was hardly possible for the Court to omit taking cognizance of.”

I have found a case after 1936, it is R v Logan (1974) Crim LR 609. A man on being convicted shouted from the dock, that it was “a carve up”, was held to be a contempt of court.

But why am I telling this?

Was Matthias Chang charged with contempt for discourtesy to the Bench?

I should think so. It was crass impertinence of him to behave in such an unruly manner towards a judge. As a lawyer he should know better than to be discourteous to the court.

I should think so. It was crass impertinence of him to behave in such an unruly manner towards a judge. As a lawyer he should know better than to be discourteous to the court.If I remember correctly he was charged with disrupting the court proceedings while giving evidence as a witness by stomping out of the witness box in a huff and left the court because the judge refused to allow him to deliver a submission or speech from the witness stand.

The only modern case (post 1936) of disruption of court proceedings that I am aware of is the case of Morris v Crown Office [1970] 2 QB 114 where the English Court of Appeal allowed an appeal against their sentence of imprisonment imposed on Welsh students who had disrupted court proceedings. Davies LJ said, at page 127:

On occasions one has the misfortune to encounter someone who makes a disturbance in court. Usually when that happens it is a case of a disappointed litigant who, from a sense of rage or disappointment at the result of his case, loses control of himself and gives vent to his feelings by an outburst either by word of mouth or physically.In Balogh v St Albans Crown Court [1975] QB 73, a young man was sentenced by Mr. Justice Melford Stevenson to six months’ imprisonment for contempt of court by planning to release laughing gas into the court to disrupt proceedings. He was released by the Court of Appeal because his conduct was not a contempt as he had not disrupted court proceedings. His plan was foiled by the police.

So now we know that the atrocious behaviour of Matthias Chang in court is a contempt in the face of the court. As he did not appeal against the sentence, could it be assumed that he was happy with the sentence of one month’s imprisonment?

Had he appealed, who knows, he could have succeeded following Morris v Crown Office.

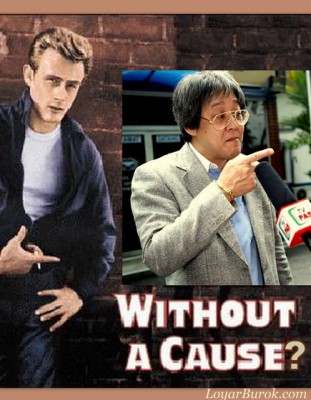

I suppose he wants to be a martyr without a cause.

courtesy of Loyarburok.com. Article written by N H Chan, who was a former Court of Appeal judge before retiring.

No comments:

Post a Comment